Articles

Emigration & The Irish Diaspora

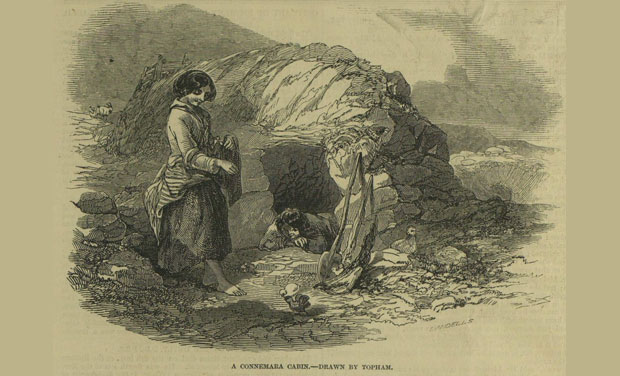

In the early 1800s Ireland’s population was growing at an alarming rate, so much so that by 1841 the population of the island was more than 8 million. At this same time the combined population of England, Scotland and Wales was just 18.5 million. Ireland was under British Rule, the vast majority of land belonged to a small minority of landowners, and much of the population lived in third world conditions.

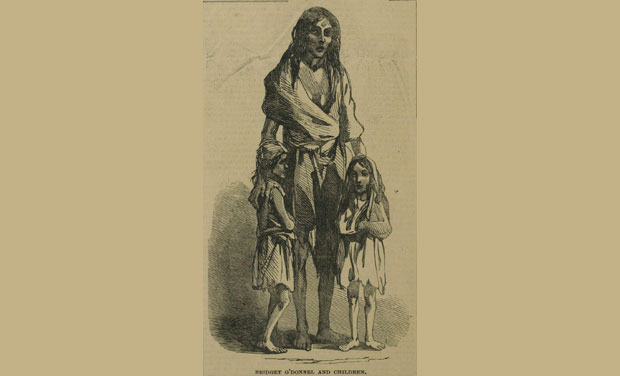

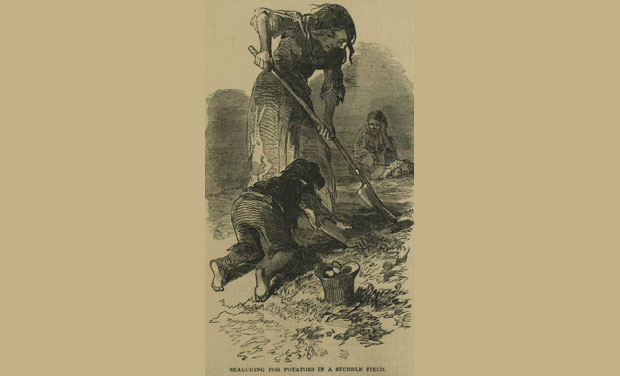

The poorest people in the country had become heavily dependent on the potato as a food source. The humble and highly nutritious potato could be grown in damp conditions, on the poorest of land and gave great yields (6 to 8 tons per acre). With milk added, it formed a balanced diet and facilitated the shift in population density in Ireland from east to west, and from good land to poor land. By the 1830s as many as 3 million "potato people" relied on the tuber for over 90% of their calorie intake. The scene was set for disaster!

The Great Hunger, 1845-52

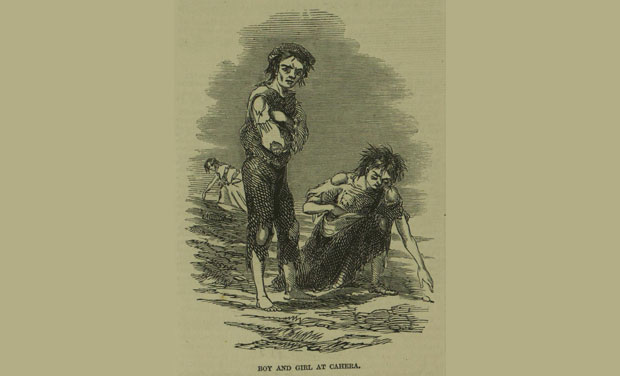

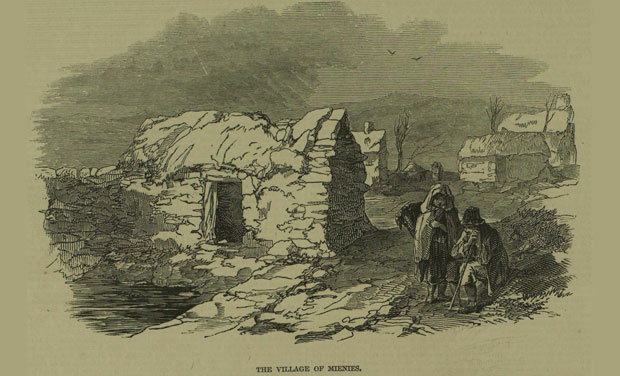

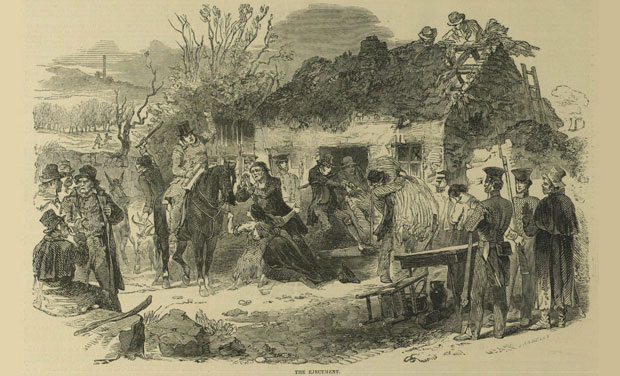

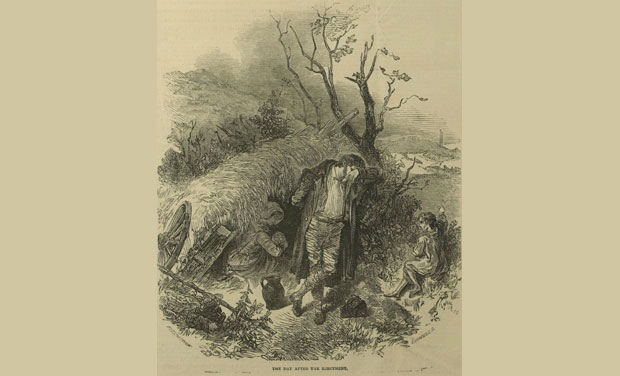

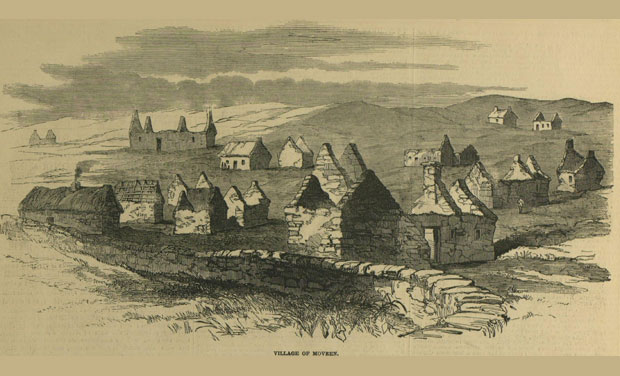

Between 1845 and 1849 the Irish potato crop was ruined three times by a fungal disease, commonly called "potato blight". Almost overnight, Ireland was plunged into a state of desperation. There were other food sources, of course, but the fact was that the poor could not afford to buy it. Large-scale exportation of grain and livestock to Britain continued whilst thousands starved. To compound matters, the British Government was slow to react, and Anglo-Irish landlords engaged in the mass eviction of those who could not afford to pay their rents. Disease and infection spread rapidly through a population weakened by starvation, the old and the very young being particularly vulnerable.

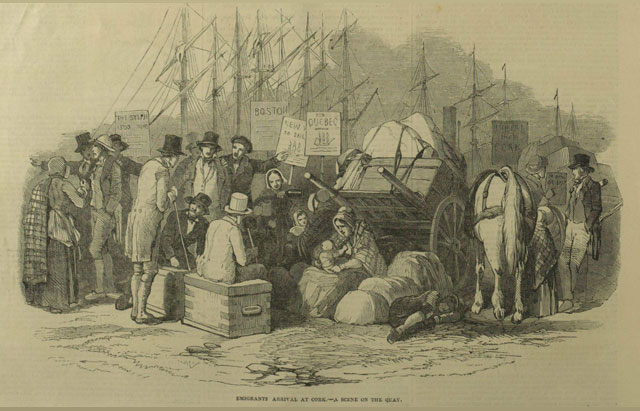

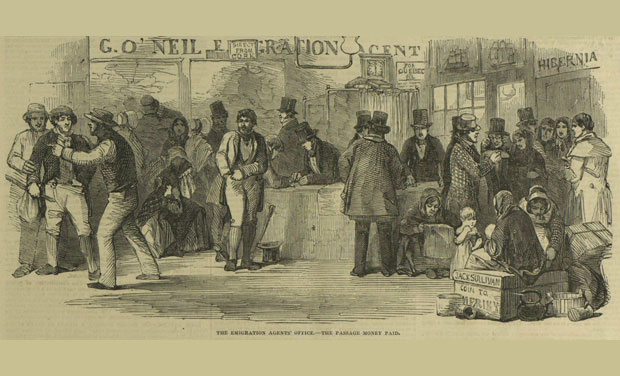

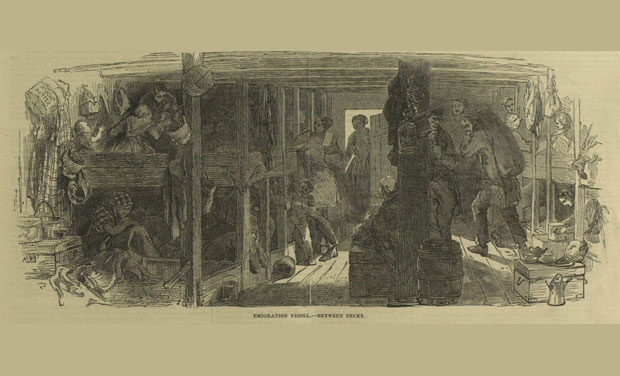

Mass Emigration

The Great Hunger was the defining event in the history of modern Ireland. As a result of death and mass emigration (particularly to North America & Britain) Ireland’s population fell by 2 million. In the western province of Connacht the population fell by almost 30% between 1841 and 1851. The effects were felt in Leeds, too, as the Irish-born population of the town more than doubled between 1841 and 1861.

By 1890 two of every five Irish-born people were living abroad. By the end of the century the population of Ireland had almost halved, and it has never regained its Pre-Famine level. From the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922 until the 1970s another 1.5 million people left independent Ireland, the vast majority travelling across the Irish Sea to take part in the post-war reconstruction of Britain.

The Irish Diaspora

These emigrants, their children and grandchildren make up what is known as the Irish Diaspora. This global Irish family includes many prominent members:

- Car manufacturer & businessman, Henry T. Ford,

- US Presidents Kennedy, Nixon, Carter, Regan, Bush Sr., Clinton, Bush Jr. & Barack Obama

- Australian folk hero Ned Kelly

- Outlaw William McCarty (aka Billy the Kidd) & his captor, Pat Garrett

- Actors Lucille Ball, Maureen O’Hara, John Wayne, Harrison Ford, Bill Murray & Will Ferrell

- Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara

- Boxers Cassias Clay (aka Muhammad Ali) & James J. Braddock (aka The Cinderella Man)

- Princess Grace of Monaco & Princess Diana of Wales

The Irish Diaspora in Britain also throws up some surprises. In sport it includes not only John Aldridge and Mark Lawrenson who played international football for Ireland, but also England internationals Wayne Rooney and Aaron Lennon. British comedians of Irish descent also abound and include Spike Milligan, Billy Connolly, Steve Coogan, Peter Kay, Jimmy Carr, and Frankie Boyle. Other popular entertainers include Paul O’Grady (aka Lilly Savage), Ant (McParland) & Dec (Donnelly), and DJ Chris Moyles. Alistair McGowan and Barbara Windsor, to their surprise, recently had their roots traced back to Ireland on the popular TV show Who Do You Think You Are? In politics, former British Prime Ministers of Irish lineage includes Arthur Wellesley (aka Duke of Wellington, 1828-30), James Callaghan (1976-79) and Tony Blair (1997-2007).

Ireland’s greatest contribution to British culture is undoubtedly the role her sons and daughter have played in the music industry. Without Irish emigration to Britain there would be no Beatles (John Lennon, Paul McCartney & George Harrison), Dusty Springfield (Mary Isabel Catherine Bernadette O’Brien), Dexys Midnight Runners (Kevin Rowland), Sex Pistols (John Lydon), Pogues (Shane McGowan), Kate Bush, Elvis Costello (Declan MacManus), Boy George (George O’Dowd), Smiths (Steven Patrick Morrissey, Johnny Marr, Andy Rourke & Mike Joyce), Oasis (Liam & Noel Gallagher, Patsy McGuigan & Tony Carroll), Libertines (Peter Doherty), or Decemberists (Colin Meloy). Hard to image Modern Britain without these icons!

The Irish in Leeds

The origins of the Leeds Irish community can be traced to the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars (1799 – 1815), which seen a sharp rise in emigration from Ireland. These pioneers settled close to the centre of Leeds (in and around Kirkgate) and then gradually moved eastwards to dominate an area around Richmond Hill, known as "The Bank". This early community was greatly boosted in numbers in the late 1840s and throughout the 1850s with the arrival of emigrants fleeing the horrors of famine in Ireland. In the following decades, the Irish were joined by growing numbers of Jewish settlers from Eastern Europe, the majority of whom came from the districts around Kovno (then in Poland, today in Lithuania), who played a significant role in the expanding ready-made clothes trade in Leeds. The Leylands district became synonymous with the Jewish community and the clothing trade.

The Bank remained the focus of the Irish community until the early decades of the 20th century. Extensive slum clearances in the 1930s dispersed the community from its traditional home in the east end of Leeds. From the late 1940s onwards more and more Irish arrived into Leeds and a vibrant community thrived. These Irish differed from those arriving in the previous century in that they were not fleeing desperate circumstances but were themselves making the decision to emigrate. They were also better educated and brought a wide range of skills with them which benefited the local economy. Many of these emigrants were raised on farms and were well used to physical labour, so they brought to the local labour market a healthy mix of brain and brawn. For the mostpart the Irish remained within a 5 kilometre radius of the city centre, with concentrations to the north-east in and around Quarry Hill, Burmantofts, Leylands, Sheepscar, Chapeltown, and Harehills.

The Irish were not the only migrants making their way to Leeds. In the 1940s and 1950s Polish, Ukrainian and Hungarian refugees from the Soviet Bloc arrived in the city. And, beginning in the late 1950s and continuing on a large scale until the 1970s, thousands of families from the "New Commonwealth" countries (Pakistan, India, West Indies & former British territories in East Africa) arrived, like the Irish, in search of work and an improved standard of living. They too moved into inner-city Leeds.

By 1971 the Irish community numbered almost 31,000 persons of whom the majority lived in twelve inner-city wards (Beeston, Burmantofts, Chapel Allerton, City, Gipton, Harehills, Headingley, Holbeck, Hunslett, Richmond Hill, Scott Hall & Woodhouse). In fact, in 1971 there were more Irish per square kilometre in inner-city Leeds than in Co. Mayo!

More recently the Irish community has moved a little further from the inner city. In 2001 North Gipton and Fearnville were recorded as having the highest concentrations. These areas boarder other areas formerly associated with the Irish community including Roundhay, Oakwood and Harehills. There are also Irish clusters much further out in Oulton & Woodlesford and Scarcroft.

The following pages explore the experience of the Irish in Leeds using historical narrative and photographs to evoke a sense of their past.

RECOMMENDED READING:

HISTORY OF LEEDS

S. Burt & K. Grady, The Illustrated History of Leeds, Derby, 2002.

D. Fraser (ed.), A History of Modern Leeds, Manchester, 1980.

D. Thornton, Leeds: The Story of a City, Ayrshire, 2002.

IRISH IN BRITAIN

G. Davis, The Irish in Britain, 1815–1914, Dublin, 1991.

E. Delaney, The Irish in Post-War Britain, Oxford, 2007.

M. J. Hickman (ed.), History of Irish in Britain: A Bibliography, London, 1986.

J. A. Jackson, The Irish in Britain, London, 1963.

K. O’Connor, The Irish in Britain, London, 1972.

A. O’Day (ed.), A Survey of the Irish in England (1872), London, 1990.

R. Swift & S. Gilley (eds),The Irish in Victorian Britain , Dublin, 1999.

R. Swift & S. Gilley (eds), The Irish in Britain, 1815–1939, London, 1989.

IRISH IN LEEDS

Dr. P. Bell, “Leeds: The Evolution of a Multi–Cultural Society”, British Council of Churches, 1982.

T. Dillon, “The Irish in Leeds, 1851–61”, The Thoresby Miscellany, 1979, pp. 1–28.

D. & H. Kennally, “From Roscrea to Leeds”, Tipperary Historical Journal, 1992, pp. 122–31.

B. McGowan, Taking the Boat: The Irish in Leeds: 1931-81. An Oral History, Killala, 2009.

M. Patterson, The Ham Shank, Bradford, 1993.

C. Silva & B. McGowan, Róisín Bán: The Irish Diaspora in Leeds, Leeds, 1996.

Leaving Home

By 1951 there were just over 6,000 people born on the island of Ireland living in Leeds. So why did so many Irish people leave Ireland and choose to go to Leeds?

In the mid-1930s the population of the island of Ireland was 4.25 million. In the Irish Free State (south) the total population was just under 3 million, of which the vast majority were living in the countryside, or in country towns and villages. At this time Ireland was a poor country, and the levels of poverty in many isolated rural areas were exceptional by western standards.

By the 1940s the conditions of rural life in Ireland had become unacceptable to many country people; few rural houses had electricity, running water, or lavatories. A lack of public transport and recreational facilities were also causes for complaint. Through newspapers, radio and travel, Irish people were becoming more aware of the contrast in their way of life and that in other countries, including Britain, especially in urban areas.

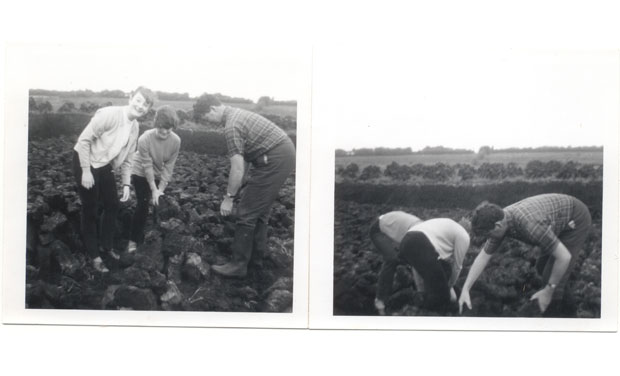

The widespread availability of work in wartime Britain, and in reconstruction of Britain in the decades that followed, was a great incentive for emigration and allowed Irish emigrants to earn relatively good wages quickly. Many men followed the well-trodden path of the seasonal agricultural migrant to the farms and fields of Yorkshire, Lancashire and Lincolnshire, and eventually opted more regular and better-paid work in the nearby cities.

As a result of emigration, Ireland’s rural population was decimated, with huge numbers leaving the western seaboard counties (Donegal, Mayo, Galway, Cork & Kerry) and the boarder counties of Leitrim, Cavan and Monaghan. Emigration peaked during the 1950s. In 1956 the population of the Irish Republic fell to a mere 2.9 million (its lowest since reliable enumeration began in 1841). The following year it is estimated that 58,000 people left the country: an average of 1,115 people a week!

The City of Leeds with its numerous shopping arcades, cinemas, parks, libraries, and extensive transport system was an attractive destination for Irish emigrants. More importantly, work was plentiful in and around the City, and a number of large-scale engineering projects (such as the construction of Quarry Hill flats, building of Council Estates, the redevelopment of St James’s University Hospital, and motorway construction throughout Yorkshire) attracted Irish labour. Later Irishmen in Leeds would establish their own construction firms and hire predominantly Irish labour. Irish women also found work plentiful in the city’s factories, hospitals, shops, and restaurants, and on the buses. Many Irish women, and often their children, worked in the city’s "silver service" industry.

Up to the 1960s the new Irish state remained a mainly rural, Catholic and conservative society with high levels of emigration. The numbers of Irish in Leeds swelled from around 6,200 in 1951 to 10,300 in 1971. An economic boom in Ireland in the late 60s and early 70s slowed the flow, and many returned to live in Ireland with their young children born in England. This was short-lived however and was followed by economic crisis in the 1980s and another tide of emigration flowed eastwards to Britain.

The Journey

Although for many young Irish men and women the move to Britain was inevitable, those who left had mixed feelings. Nervousness and a sense of excitement were accompanied by a sense of loneliness for family and home. Goodbyes were said, tears shed and then the journey began. The following poem sums up some of the migrant’s concerns and worries:

I go without the heart to go,

To kindred that I hardly know.

Drink, neighbour, drink a health with me

Farewell to barn and stack and tree

Five hours will see me stowed aboard,

The gang-plank up, the ship unmoored.

Christ grant no tempest shakes the sea

Farewell to barn and stack and tree

The Emigrant by Joseph Campbell, 1913

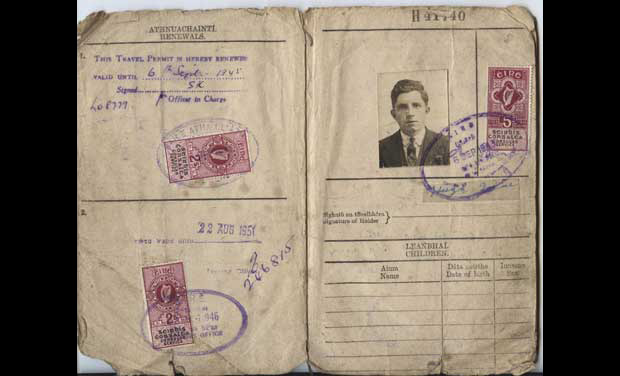

Today the journey from Ireland to England can be made in under an hour by air, or under two hours by sea, but in the past the journey took a day or more to complete. Emigrants made their way to the nearest large town, took the bus or train to Dublin, from where they boarded a boat to Holyhead or Liverpool; from here trains and buses connected to urban centres across Britain. The sea-crossing could be tracherous in bad weather. The Princess Maud, which operated between Dun Laoghaire and Holyhead from 1947 to 1965, was well-known to Irish emigrants; having no stabilisers the ship had a bad reputation for rough crossings.

First Impressions

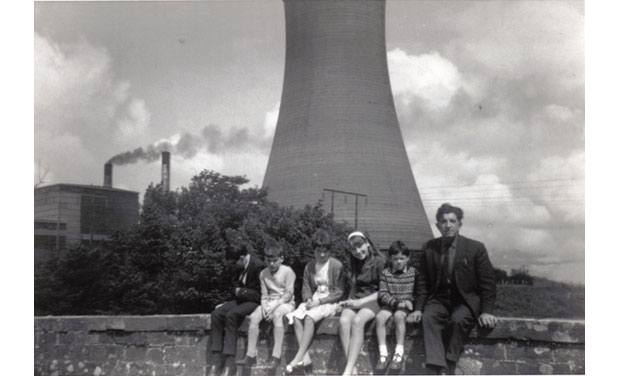

Irish people were well informed about life in urban Britain from newspaper accounts, emigrant letters and stories. Nonetheless for many new emigrants life in urban Britain came as a culture shock, particularly to those from a rural background. After the long journey from Ireland the train made its way through the Pennines and then slowly through the suburbs of Leeds and into the city centre. For many Irish emigrants Leeds City train station would be their first experience of urban Britain, and first impressions of Leeds do not always paint a pretty picture, often recalling a dirty, smoky and smelly city. The Industrial Revolution had blackened the city and its buildings greatly contrasted with the whitewashed farmsteads of rural Ireland. The hustle and bustle of the city greatly contrasted to the pace of rural life. The sense of enclosure made those used to wide open spaces feel uneasy. Others recall the wonder of first seeing people of different skin colour.

RECOMMENDED READING:

LIFE IN IRELAND

C. Clear, Women of the House: Women’s Household Work in Ireland 1922–1961, Dublin, 2000.

J. Healy, No–one Shouted Stop!, Achill, 1988.

D. Keogh, et al, The Lost Decade: Ireland in the 1950s, Dublin, 2004.

IRISH EMIGRATION TO BRITAIN

E. Delaney, Demography, State and Society: Irish Migration to Britain, 1921–71, Liverpool, 2000.

D. MacAmhlaigh, An Irish Navvy: Diary of an Exile, Cork, 2003.

D. MacRaild, The Great Famine & Beyond, Dublin 2002.

Settling In

On arrival, some emigrants were lucky enough to be met by family members or friends, who were already living in the city and who could help out with finding a bed and work. Familiar faces and voices eased the transition from rural life in Ireland to urban life in Britain, and eased feelings of loneliness and isolation.

Others arrived with nothing more than the address of an Irish landlady, priest, or site foreman. These points of contact were invaluable. Irish landladies rented whole houses and sublet rooms to young Irishmen, often acting as a substitute mammy and banker. Priests were often very active in all aspects of the community and could provide useful advice and contacts. The foreman could ensure work, or at least point you in the direction of work.

Others arrived with no network to access, and had to rely on their own ingenuity, or luck. The local Irish Centre or Irish-run public house was also a first port of call and were places where information on work and accommodation could be sourced. Public houses were often known as "Paddy’s exchange" where information on jobs, wages and conditions were discussed.

It was usual for migrants to choose destinations where people from their locality had gone before them. Over time certain English cities became associated with particular parts of Ireland. In Yorkshire, Leeds had long been associated with emigrants from County Mayo (particularly the northern half), and Huddersfield with Irish-speaking emigrants from counties Galway and Kerry.

Communication Breakdown

It is easy to assume that Irish emigrants had little problem in communicating with the native population of Leeds, as English is spoken in both countries. This is not strictly true. Travel, education, radio and television have all played a part in eroding local dialects and accents, but half a century ago many Irish emigrants had initial difficulties understanding the Yorkshire accent and dialect. And many Yorkshire folk struggled with the array of Irish accents.

Yorkshire t’English Dictionary

| Ey up | Hello/Watch Out! |

| Now then | Hello |

| Nowt | Nothing |

| ’Ow do | Hello |

| Owt | Anything |

| Reet | Right |

| Tin’t | It isn’t |

There were also many Irish, from the western seaboard in particular, who spoke only Irish and had little or no English on arrival. Imagine not being able to read street signs, or to ask for directions! The result was often frustration and alienation. It should be remembered that Irish people who spoke only Irish often felt alienated from their fellow Irishmen who spoke only English.

Irish English Dictionary

| Cead Míle Fáilte | Welcome |

| Ceol | Music |

| Dia Duit | Hello |

| Slán Abhaile | Goodbye |

| Sláinte | Health |

Keeping in Touch

In the days before telephones were common household conveniences, emigrants kept in touch by writing home. Letters told of new lives and new experiences. Once a job was secured these letters were often accompanied by a cheque, postal order, or indeed cash. Irish landladies often encouraged young men to put aside money to send home, or held it in trust for them, and older emigrants offered gentle reminders of their duty to their families back in Ireland.

The Irish have long been recognised for their generous remittances to their homeland. In the 1950s and 1960s Irish emigrants sent back around £3.5 billion from Britain to the country of their birth.

Rural families and communities were in many cases dependent on this money. This increase in family income often made it unnecessary for younger siblings to emigrate, but in other cases it enabled them to do so. Houses were improved, slate roofs gradually replaced thatch, farms were enlarged, and farm machinery was bought. As well as money clothes, shoes and other gifts were sent back to Ireland. Money brought home on holidays injected further finance into the local economy.

Emigrant remittances were also important to the Irish national economy. In 1961 the amount of money returned to Ireland from her sons and daughters in Britain equalled that which the Irish government spent on education. The social effect of these returns was to bring about greater equality in the distribution of wealth.

RECOMMENDED READING

IRISH IN BRITAIN

U. Cowley (ed.), McAlpines Men: Irish Stories from the Sites, Dublin, 2010.

U. Cowley, The Men Who Built Britain, Dublin, 2001.

E. Delaney, The Irish in Post-War Britain, Oxford, 2007.

J. A. Jackson, The Irish in Britain, London, 1963.

K. O’Connor, The Irish in Britain, London, 1972.

Coming Together

As well as suitcases Irish emigrants brought their cultural traditions across the Irish Sea to Britain. Along with religious practice, Gaelic games, the Irish language, and traditional music, song and dance have been the great markers of Irish identity abroad.

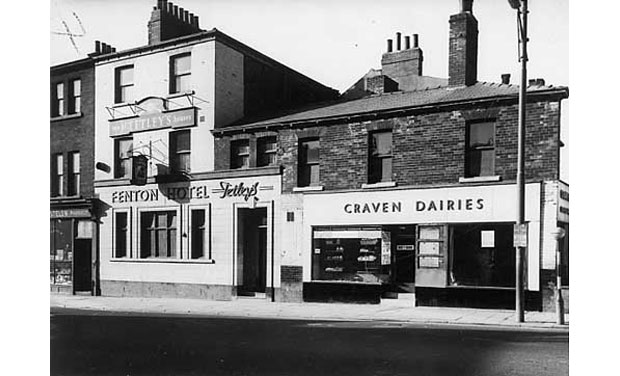

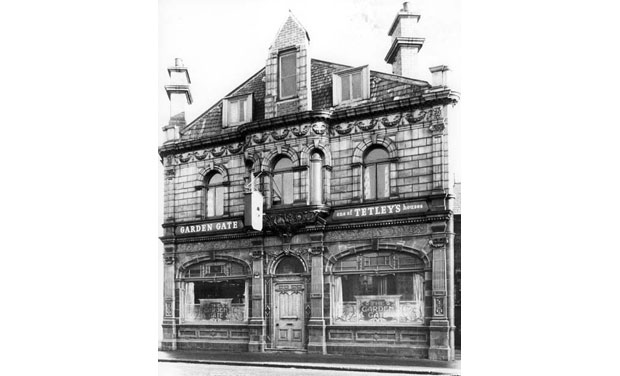

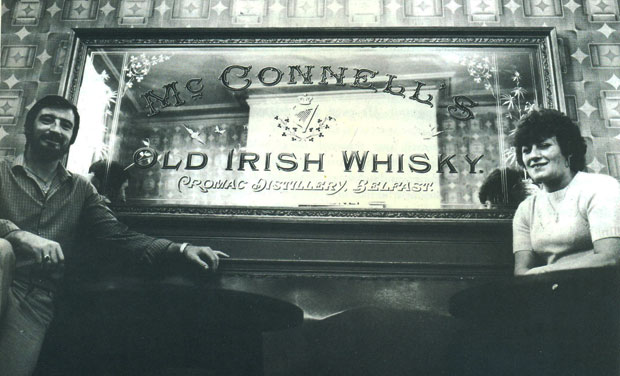

In the early 1900s the impoverished and shrinking Irish community had few social venues in Leeds in which to gather, apart from the Irish National Club, Lower Briggate (fondly known as the "Old Nash") and a few church halls. To compound matters much of the community lived in cramped conditions, in small houses or rented rooms, which were not suitable for large get-togethers. As greater numbers poured into the city from the 1950s Irish-run public houses sprung up in the areas in which the new arrivals settled. In an absence of other suitable venues these became the centres for the Irish social scene. As the Irish community gradually strengthened in numbers and confidence, they acquired better venues and playing pitches, and established organisations for the promotion and teaching of Irish traditions.

Gaelic Games

Traditional Irish sports, such as Gaelic football and hurling, have long been played in Leeds. Until the late 1940s these were played informally in local parks (such as Potternewton Park, Chapel Allerton) on Sunday afternoons between gangs of Irish lads. Comically, there is a story about one such game of hurling being broken up by the police after a panicked report about Irishmen attacking each other with "sticks"! In 1948 the Yorkshire County Board of the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) was established, and several clubs were formed in Leeds. Newly arrived emigrants joined clubs to find old friends and make new ones. As in Ireland, county and club loyalty are strong, with emigrants from particular counties choosing to join clubs where their fellow countymen dominated. Although, hurling as a competitive sport died out in Leeds, football remains strong. Today, there are 5 senior football clubs in Leeds: St. Anthony?s, St. Benedict?s Harps, Hugh O?Neills, John F. Kennedy?s & Young Ireland?s. There is a healthy mix of camaraderie and rivalry between the clubs, and matches are competitive.

Many Irish in Leeds are great supporters of Leeds United, and many Irish players have donned the white strip of Leeds over the decades, most notably Johnny Giles, John Sheridan, Gary Kelly, Ian Harte and Robbie Keane. And honorary Irishman Jack Charlton, who brought unprecedented footballing success to the Republic of Ireland, spent his best playing years at Leeds United. Gaelic games have also been played at Elland Road. In 1987 the Yorkshire County Board of the GAA organised a match between Mayo and Dublin.

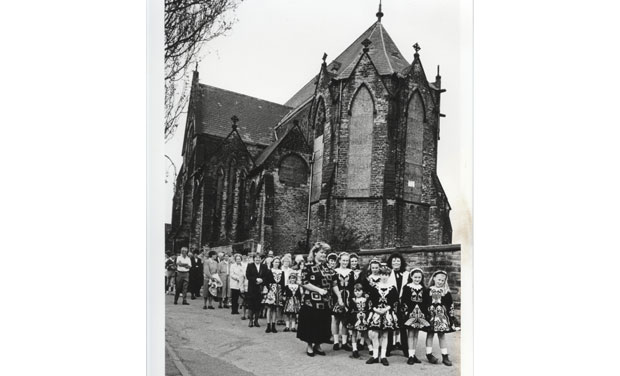

Music, Song & Dance

Irish public houses became the centre for Irish traditional music and song, with particular pubs gaining reputations for their "sessions", such as the Regent Hotel (Leylands), Old Roscoe (Sheepscar), and Fountain Head (Burmantofts). The Irish traditional music pub session is in fact a British phenomenon. Traditionally, in Ireland the music venue was by the hearth in the home, but in the absence of a hearthside Irish emigrants turned to the warmth of the public house. Here tunes and song from home were heard and exchanged. The Leeds Branch of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Eireann (roughly Association of Irish Musicians) was formed in the Regent Hotel in 1969. Over time, several schools of Irish dance were formed in the City.

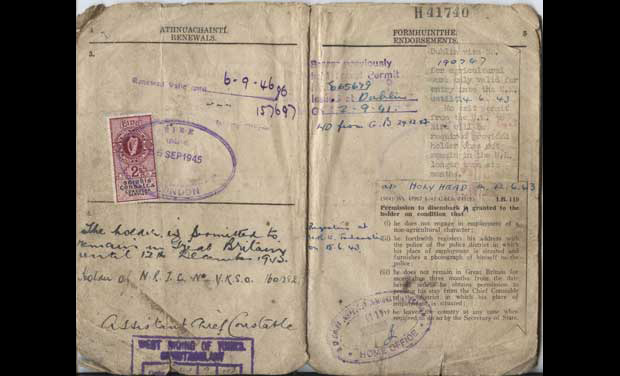

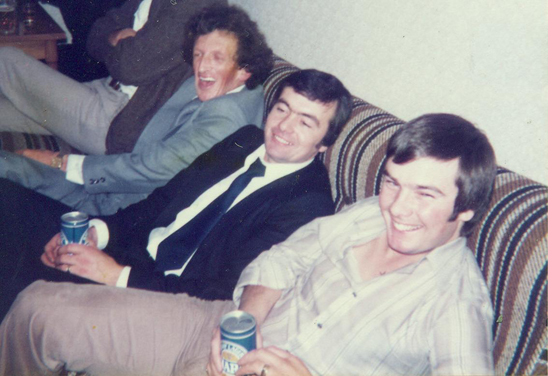

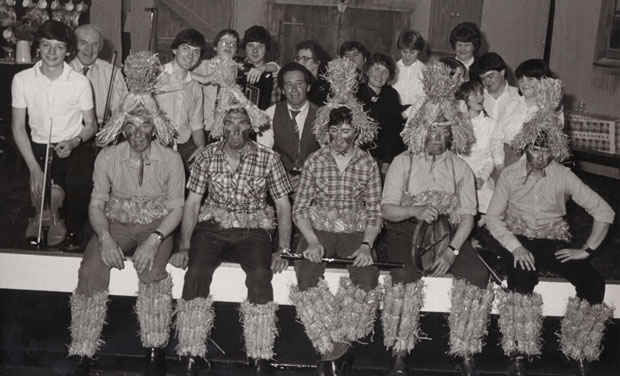

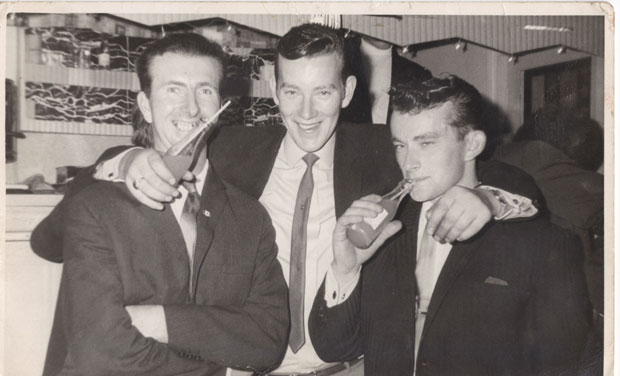

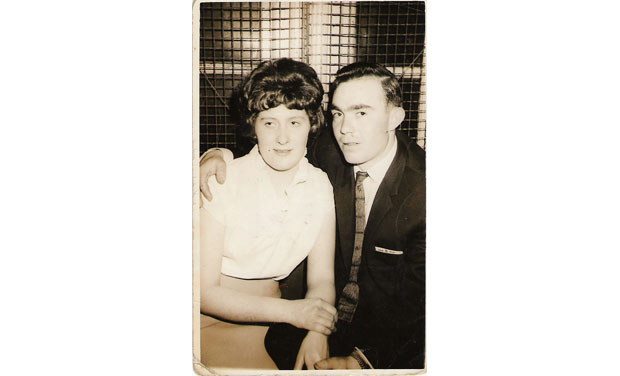

Pubs, Clubs & Dancehalls

Irish emigrants to post-war Britain were primarily young and single, with as many women as men leaving, which was unusual in a European context. In response to the growing numbers of young Irish people arriving into the city, particularly from the 1960s, Irish landlords began taking over public houses in areas in which the Irish were settling. There was a particular concentration around the City Centre, and moving north-eastwards around Leylands, Burmantofts, Sheepscar, and Harehills. The pubs varied in size, standard and reputation. Depending on the landlords county of origin some pubs became associated with particular Irish counties. In other non-Irish pubs, there was often an unofficial "Irish corner". Irish-run pubs were not of, of course, exclusive to the Irish, and the native community mixed freely. University lecturers and students with an interest in folk music were also amongst the regular visitors to pubs with traditional Irish music.

St Francis, Holbeck, and the Shamrock, Kirkgate, were the popular Irish dancehalls in Leeds and were well-known in Ireland and throughout Yorkshire. In the 1960s, during the height of the showbands era, the Shamrock drew bus loads of young Irish men and women from all over Yorkshire, and many married couples owe their thanks the Casey?s from Co. Kerry who opened this dancehall.

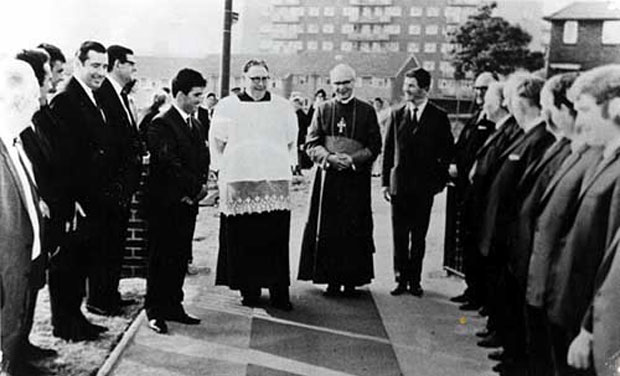

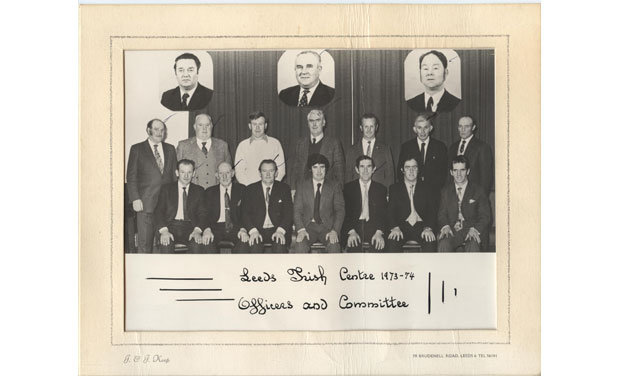

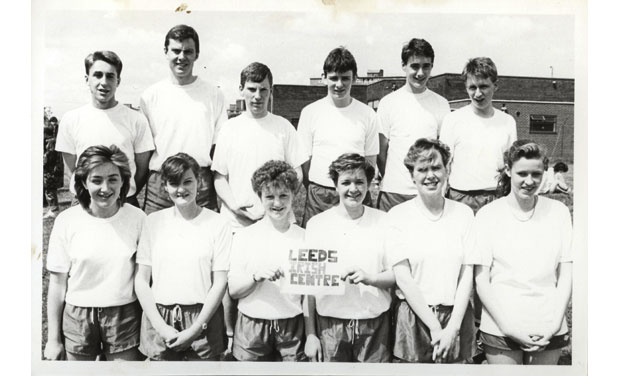

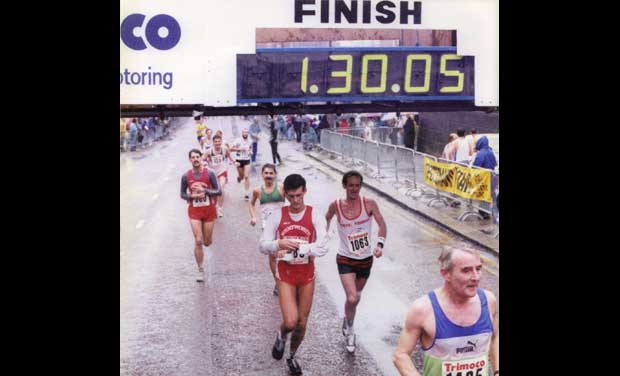

Leeds Irish Centre

In the late 1960s Leeds Councillor and Irish National Club committee member Michael Rooney acquired 3 acres of land off York Road, close to the original home of the Leeds Irish Community, and with the backing of famous local brewery Tetley?s the first purpose-built Irish centre in Britain was constructed. The new centre opened in 1970 and it quickly became home to the various Irish cultural organisations, offering greater room and comfort to socialise than the small pubs and church halls which had served until then. Over time the Leeds Irish Centre expanded to include a games room, members meeting room, function rooms, playing pitches and sports facilities.

One of the Leeds Irish Centre?s great successes has been its "Tuesday Club". The weekly Club caters for the city?s ageing Irish community providing lunch and an afternoon of entertainment, including bingo, live music and dancing. Group holidays and outings are also organised. It was established LIC manager Tommy McLoughlin in 2000, and is staffed by more than 30 volunteers who cater for its 200 weekly members.

Associations & Societies

As the Irish settled in Leeds they formed various clubs, societies and organisations as a result of various interests, passions and causes. Over time people from the same counties and localities came together to form associations, such as Leeds Mayo Association, Leeds Attymass Association and Leeds Knockmore Association. The founders recognised the importance of maintaining connections with friends and relatives. The Leeds Irish Welfare Society and, later, Leeds Irish Health & Homes concerned themselves with the welfare and well-being of the Irish community, particularly those who were marginalised or had found themselves in difficult circumstances.

More recently, several Irish cultural organisations have appeared on the Leeds scene. Formed in 2002, Leeds Irish Historical & Cultural Society, which owes it roots to the Mount Saint Mary?s History Group, is concerned with the history of the Leeds Irish community and family history. In the same year Lucht Focail (meaning "People of the Word") Irish Writers? Group was formed, which is dedicated to encouraging and promoting the written word in all its literary forms - poetry, short stories, novels and drama. And not forgetting the Irish Arts Foundation, which developed from the earlier Harehills Irish Music Project, the aim of which is to raise the profile of Irish music and the arts throughout Britain and to celebrate the many contributions that Irish people have made to British society.

Irish Days

Long gone are the dark days when Irish culture and heritage were quietly tended to in small pubs and parochial halls. Since the late 1990s two Irish festivals have been developed either side of the River Aire. The Leeds Irish Festival, which is located in Beeston in South Leeds, annually showcases all that is best about Irish music, song, dance, sport, and food. The first St. Patrick?s Day parade took place in Leeds City Centre in 2000 and has since grown to become one of the City?s most vibrant cultural events. Both events allow the Leeds Irish Community to take to the streets and flaunt its heritage.

RECOMMENDED READING :

IRISH CULTURE

H. Brennan, The Story of Irish Dance, Dingle, 1999.

J. Cleary & C. Connolly (eds), Cambridge Guide to Modern Irish Culture, Cambridge, 2005.

Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (Leeds), Leeds 25: Silver Jubilee, Leeds, 1994.

Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (Leeds), Leeds 20: Twenty Years A-Growing, Leeds, 1989.

Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (Leeds), Celebrating 40 Years of Leeds: 1969 - 2009.

E. Corry, An Illustrated History of the GAA, Dublin, 2006.

M. Cronin, et al (eds), The GAA: A People?s History, Cork, 2009.

R. Hickey, Irish English: History & Present Day Forms, Cambridge, 2011.

Leeds Irish Centre, Celebrating 40 Years, Leeds, 2010.

M. McCarthy, Passing It On: The transmission of music in Irish culture, Cork, 1999.

E. Purdon, The Story of the Irish Language, Cork, 1999.

F. Vallely (ed.), The Companion to Traditional Irish Music, Cork, 2010.

Rites of Passage

Ireland is a Christian country, with the vast majority of its people traditionally belonging to the Roman Catholic Church. There is also a significant population in Northern Ireland belonging to the various Protestant churches (Presbyterian Church, Church of Ireland & Methodist Church).

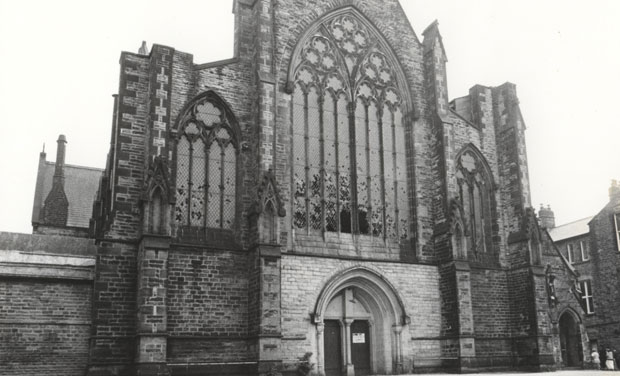

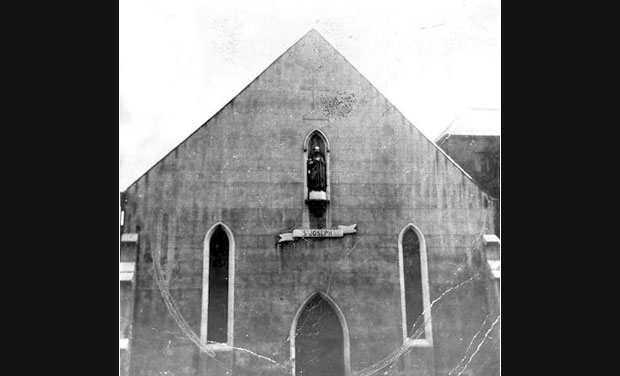

The vast numbers of Irish arriving in Leeds from the 1820s greatly swelled the Catholic population of the town. New churches were built in 1831 (Saint Patrick’s, Burmantofts) and 1857 (Mount Saint Mary’s, Richmond Hill) to serve the Irish who for the most part settled in the east end of Leeds.

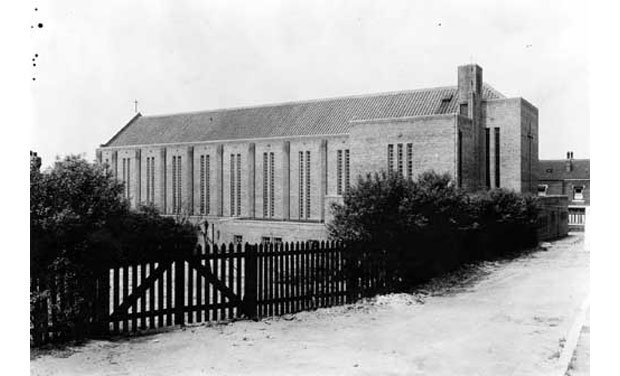

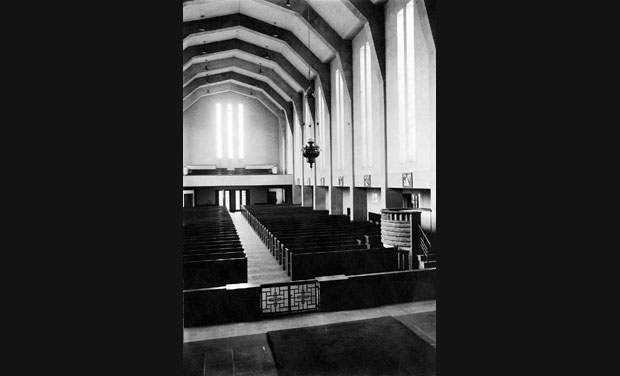

Slum clearances in the city centre in the 1930s meant that the Irish community was dispersed from its traditional home and as a result news parishes were created and churches built across the city, including Saint Augustine’s (Harehills) and Church of the Holy Rosary (Chapeltown) both completed in 1937.

The 1950s witnessed an increase in the number of new parishes being set up, partly due to the expansion of the outer suburbs but also to cater for the increasing Catholic population which had been boosted not only by the Irish, but also by Polish and Italian migrants. As the Irish community grew so did its number of priests; in 1950 almost two thirds of the Catholic clergy in Leeds were originally from Ireland.

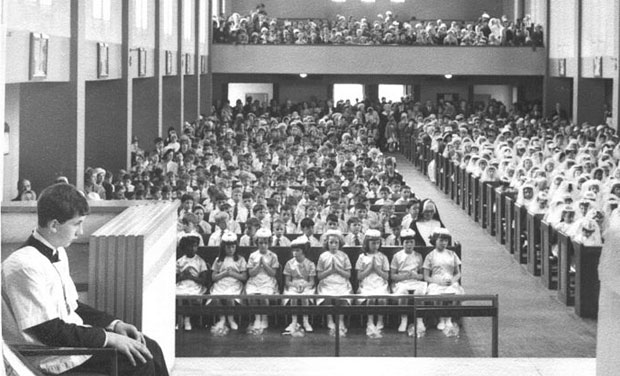

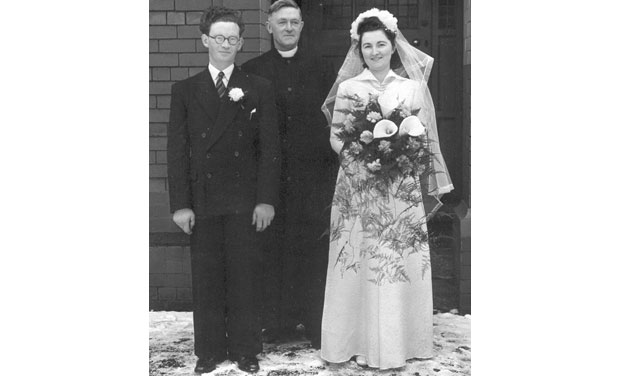

Irish Emigrants & the Church

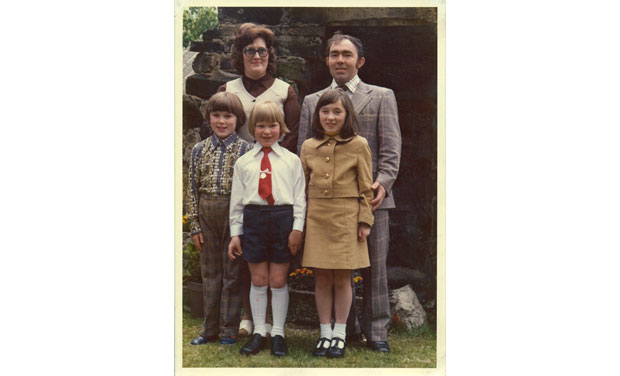

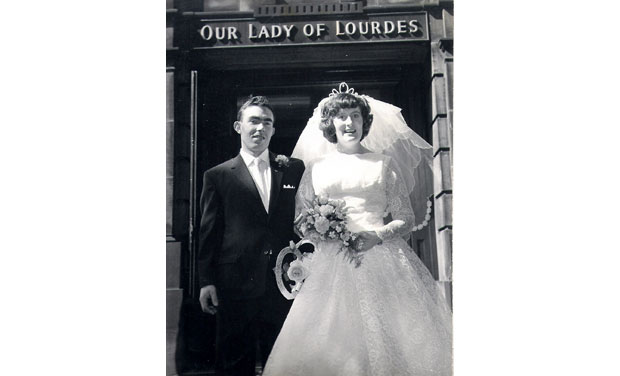

Whilst some Irish emigrants lapsed in faith for many religion remained important. Personal and communal prayer were the mainstays of Catholicism, and provided comfort in difficult times. Through the church new arrivals integrated with those already settled in the city and with the descendants of earlier migrants. Irish families continued to intermarry which reinforced both Catholic faith and Irish cultural traditions. Religious rites of passage (christening, first holy communion, confirmation, marriage, and funerals) remained important occasions for the individual and the community as they came together to celebrate and mourn. Many people had shrines displaying statues and holy pictures in their homes.

Sunday was an important day in the emigrant’s diary. For those working 6 days in the week it was a welcome day for rest and relaxation. On Sunday mornings the everyday work clothes were replaced by the “Sunday best” as individuals and families made their way to their local church for mass. As well as being a spiritual gathering, Sunday mass was a social occasion where friends and neighbours could meet and news from home was exchanged. This was especially important in the early days of the community when there were few Irish social venues in the City.

Over time many Catholic churches across Leeds became closely associated with the Irish community, including St Anthony’s (Beeston), Our Lady of Lourdes (Burley & Hyde Park), St Patrick’s (Burmantofts), Holy Rosary (Chapeltown), St Nicholas’ (Gipton), St Augustine’s (Harehills), St Joseph’s (Hunslet) & Mount St Mary’s (Richmond Hill).

Many Irish families chose to send their children to Catholic schools, where they mixed with other Irish children and others of Irish descent. Today many children attending Catholic schools across the City bear Irish surnames, often unaware of their Irish roots.

RECOMMENDED READING:

RELIGION & IDENTITY

K. Danagher, The Year in Ireland, Cork, 2001.

S. Fielding, Class & Ethnicity: Irish Catholics in England, 1880–1939, Buckingham, 1993.

R. E. Finnegan (ed.), Catholicism in Leeds: A Community of Faith, 1794–1994, Leeds, 1994.

P. Gavan, Memories of Mount St. Mary’s Church, Richmond Hill, Leeds, 2001.

M. P. Hornesby–Smith (ed.), Catholics in England 1950–2000, London, 1999.

Fr. K. O’Shea, The Irish Emigrant Chaplaincy Scheme in Britain, 1957–82, Naas, 1985.

P. O’Sullivan (ed.), The Irish World Wide. Volume 5: Religion & Identity, London, 1996.

Hunger for Home

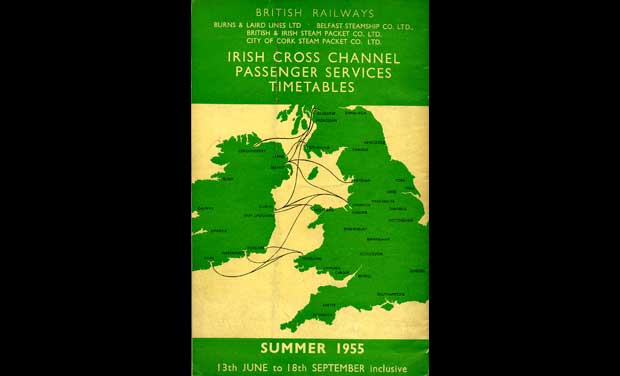

Irish emigration to Britain never had the same sense of permanence as emigration to North America. The relative nearness of the two islands meant that emigrants could keep in close contact with their families in Ireland and frequently travel home for holidays. From the middle of the 20th century improved and cheaper sea passage across the Irish Sea made visits home more feasible. Irish emigrants in Leeds were favourably placed as the city was well-connected by rail with the city ports of Liverpool and Holyhead which offered regular sailings to Ireland. The introduction of car ferries made it easier to bring the whole family to Ireland, and as air-travel became cheaper emigrants could fly from Leeds / Bradford Airport into Dublin, or directly into the smaller regional airports, such as Knock or Galway.

Holidays

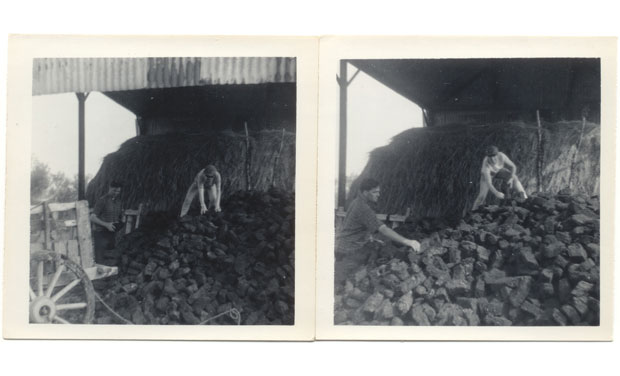

The arrival of emigrants home on holiday was cause for celebration in rural Ireland. The young and single working emigrant could afford to go home on holiday once or twice a year, often for a week or a fortnight during the summer and at Christmas. This was an opportunity to spend time with parents and family, to catch up with friends and neighbours, and also with other emigrants who were home on holidays. Information about life in urban Britain, about work and living conditions, and indeed the social scene, was shared locally and often greatly influenced others to follow in their footsteps. During the summer, in particular, the extra pair of hands to help with farmwork or on the bog was much appreciated.

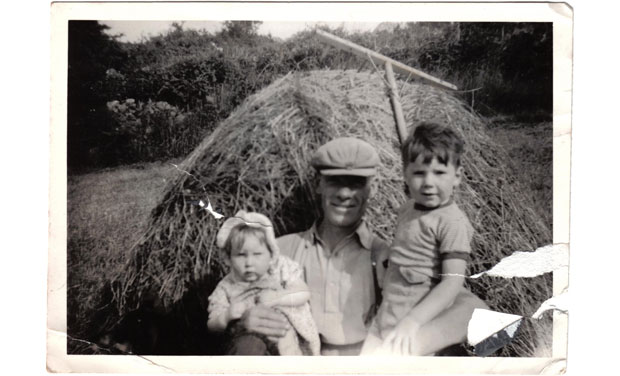

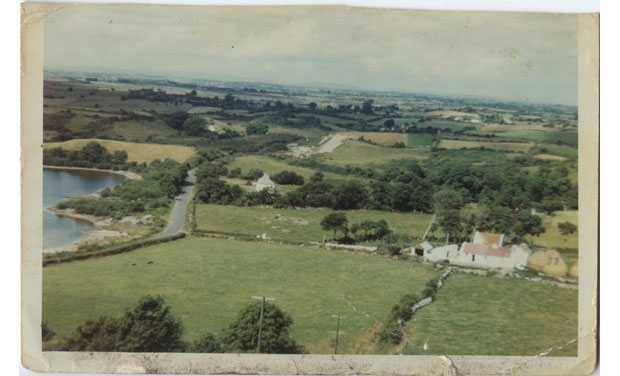

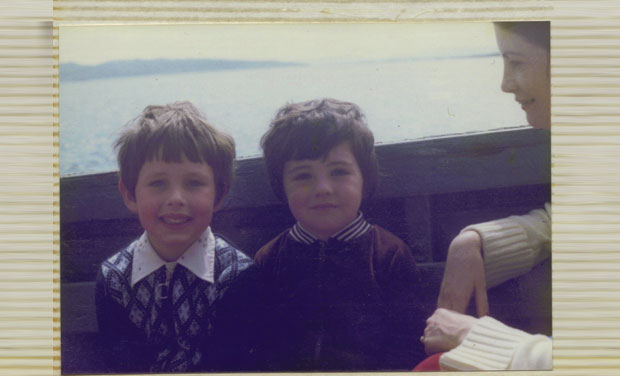

For those with young families the greater expenses involved in going home often restricted the number of trips. Women in better circumstances could spend whole summers in Ireland with their children, their husbands often staying behind to work and joining them later. Children born and raised in Leeds experienced a much different world in Ireland, and for a few short weeks rural life replaced urban life. The redbrick terraced housing and backstreet playgrounds greatly contrasted with farmsteads and open fields. Children were allowed greater freedom to roam than their parents would ever allow in the city. Grandparents, aunts and uncles made a fuss of the visitors and children were the centre of attention. They got to know their Irish cousins, who would often join them in Leeds when they were old enough to emigrate. For many these childhood holidays and the sounds and smells of rural Ireland would long remain as idyllic memories. At the end of the summer tears were invariably shed as families were again separated.

Family Ties

It was not unusual for Irish women return home to give birth, or to have their children baptised. Sometimes, too, a sister living in Ireland might go Britain to assist a sister who had given birth. There were other less joyous reasons for return trips. Emigrants returned home to care for sick or elderly family member, or to help out with farmwork during such difficult times.

It was common for emigrants to return to Ireland at short notice following the death of a loved one. The tradition of the Irish wake - where family, friends and neighbours gather to celebrate life and mourn death - was strong, particularly in rural Ireland. Emigrants often didn’t return to Britain for several days, much to the annoyance of some employers. For many, the death of parents affected the pattern of visiting Ireland, and often marked the end of "going home", particularly if all their brothers and sisters had emigrated.

Return Migration

Many Irish emigrants left with the intention of spending a few years working in Britain before returning home to settle. The reality was that most settled in Britain and gradually lost the ambition to return. Some did return, however! The 1970s witnessed a short economic boom in Ireland and as a result some emigrants took the opportunity to return to Ireland with their British-born children. The return to live in Ireland was often as difficult as the initial move to Britain, and the difficulties encountered were the exact reverse of those experienced when first migrating, such as problem adjusting to the slower pace of life, and moving from an anonymous society to one where everyone "knows your business". Irish writer Frank O’Connor wryly observed that "an Irish person’s private life begins in Holyhead!" Other problems remained the same whilst they were away: the lack of a satisfactory social life, poor economic situation and severity of the Irish winter. Many who returned soon realised that holidaying in Ireland and living in Ireland were two very different things. Some adapted, others re-migrated to Britain.

During the Celtic Tiger years, too, the unprecedented level of prosperity enticed Irish emigrants to return to their native land. At this time a different set of problems were encountered. Ireland had gone through dramatic social and economic change in a short space of time, and was virtually unrecognisable to those who had left decades earlier.

RECOMMENDED READING:

RETURN MIGRATION

G. Gmelch, “The readjustment of return migrants in western Ireland”, in R. King (ed.), Return Migration & Regional Economic Problems, London, 1986, pp. 152–170.

E. Malcolm, Elderly Return Migration from Britain to Ireland: A Preliminary Study, Dublin, 1996.

In Hindsight

Hindsight, it is said, is twenty-twenty vision, meaning that situations become clearer when you look back upon them. So, looking back, how do the Irish in Leeds feel about their decision to leave Ireland and about their lives in Britain? It is perhaps natural to nostalgically recall your childhood, and remember clearly the stresses involved in moving out of the family home. This is magnified when you are not only leaving your home, but are leaving behind your community AND country.

An old Irish saying wisely states is glas iad na cnoic i bhfad uainn (literally "green are the hills far from us") meaning roughly the same as "the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence". This it true of Irish emigration! Families were often split by migration with some members staying (or having to stay) in Ireland, and other going (or having to go) to Britain. Those who left Ireland were transformed by the experience, as were those who stayed at home. It is often the case that siblings left behind felt that they missed out on the adventure and excitement of moving to urban Britain, and that those who left were better socially and financially. It is also true that those who left Ireland often felt that those who remained had it better, getting to live their lives where they could only holiday, and often inheriting the family homestead.

The reality of the Irish experience in Britain is that the majority soon settled in and found work, made friends and met partners, married and started families. Many Irish emigrants, having left Ireland with the intention of returning eventually, adapted to life in Britain and gradually, especially as their British-born children grew up, lost the ambition to return, except perhaps for holidays or retirement. Others came to the conclusion that life had been good to them in Britain!

First Impressions

As this Untold Stories project is being launched (2011), Ireland is reeling from a three-year recession and a debt crisis, which has led to mass unemployment, resurgent emigration and an international bailout. Young people are again leaving Ireland in their droves, some following the well-trodden path to Britain, but the majority going further afield to Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Although there is the same sense of sadness at seeing family members leave home, it is a different emigration to that of the 1950s or 1980s. Close contact with home is greatly facilitated by the internet, social networking sites and mobile phones. Those currently leaving Irish shores tend to be highly skilled and well-educated and optimism prevails - the old concept of a ’brain drain’ caused by emigration being replaced with a more modern concept called ’brain circulation’ whereby people move countries acquire experience and skills before returning home. Go n-éirí an bóthar libh go léir!

RECOMMENDED READING:

IRISH IN BRITAIN: ORAL HISTORIES

C. Dunne, An Unconsidered People: The Irish in London, Dublin, 2003.

J. B. Keane, Self–portrait, Cork, 1964.

M. Lennon, et al (eds), Across the Water: Irish Women’s Lives in Britain, London, 1988.

A. Lynch (ed.), The Irish in Exile: Stories of Emigration, London, 1988.

D. MacAmhlaigh, An Irish Navvy: The Diary of an Exile, Cork, 2003.

B. McGowan, Taking the Boat: the Irish in Leeds, 1931 – 18. An Oral History, Killala, 2009.

S. Ó’Ciaráin, Farewell to Mayo: An Emigrant’s Memoirs of Ireland & Scotland, Dublin, 1991.

J. O’Donoghue, In a Strange Land, London, 1958.

R. Wall, Leading Lives: Irish Women in Britain, Dublin, 1991.